Rights of Trans Youth

Last week I wrote to the members of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta regarding their use of the notwithstanding clause to override the rights of transgender youth. If you are so included, please feel free to cut and paste this into your own letter. Email addresses to members of the Legislative Assembly can be downloaded here (linked to assembly.ab.ca) as a .CSV - this format will open in Excel or Numbers.

Dear Honourable Members of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta,

I am writing to express my deep concern and profound disappointment regarding your government’s decision to invoke the notwithstanding clause to override the rights of transgender youth. As an Albertan who values democratic accountability, bodily autonomy, and evidence-based healthcare, I find this decision alarming.

Let me be clear: every young person in this province deserves timely, appropriate medical care rooted in science and compassion. And while I am relieved any time the government claims to be “protecting kids,” I am appalled by the means used to achieve that end. Preemptively suspending Charter rights, before courts can even assess the constitutionality of your actions, is not protection. It is overreach.

Medical decisions about a child’s wellbeing belong with families, their physicians, and qualified healthcare providers, not with politicians. Gender-affirming care is not experimental, fraudulent, or dangerous; it is grounded in decades of clinical research and endorsed by major Canadian and international medical associations. The rhetoric used to justify this legislation distorts the science and misleads the public in ways that put vulnerable youth at greater risk.

By invoking the notwithstanding clause, your government is not demonstrating confidence in its policy. It is sidestepping scrutiny and signalling a willingness to override fundamental rights when politically convenient. That should concern every Albertan, regardless of their views on this particular issue.

Trans youth deserve dignity, safety, and access to appropriate medical care. Their families should be able to work with physicians—without state intrusion—to make the decisions that are best for their children’s health and futures. Anything less is a failure of governance.

I urge you to reverse course. Recommit yourselves to evidence-based policy, to constitutional norms, and to respecting the private and profoundly personal nature of medical decision-making. Alberta should be a place where rights are upheld, not suspended.

Bill 2 and the Rights of Educators

Yesterday morning I wrote to the members of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta regarding their passing of Bill 2. If you are so included, please feel free to cut and paste this into your own letter. Email addresses of Alberta MLS can be downloaded here (linked to assembly.ab.ca) as a .CSV - this format will open in Excel or Numbers.

Dear Honourable Members of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta,

I write to you as a citizen who believes deeply in public education, democratic process, and the dignity of the people who teach our children. I am compelled to respond to your passage of Bill 2 and the way in which it has been used to override the rights of the educators of this province, and by extension the rights of every citizen in Alberta.

Like many parents, I’m relieved that children are back in school. But I am appalled by the means used to achieve that outcome. Invoking the notwithstanding clause to force teachers back to work is not leadership—it is coercion. It undermines both the collective rights of educators and the spirit of collaboration that should define our education system.

It is appalling that the government has resorted to silencing professional educators who have for years raised alarms about classroom conditions, funding shortfalls, and untenable workloads. I reject the idea that progress in our schools means stripping rights rather than listening, engaging, and collaborating.

When teachers feel compelled to strike, it is not just a labour dispute—it is a warning signal that the system itself is faltering. You cannot claim to champion education while undermining the institutional trust and professional respect that the teaching profession deserves. This action risks not only the morale of teachers but the futures of the students they serve.

You have chosen a path of imposition rather than dialogue. I urge you to reconsider that choice. Respect the voices of the educators, restore meaningful bargaining, and demonstrate with your actions that you believe in the systemic strength of our public education system—not merely in rhetoric.

If indeed you are serious about strengthening Alberta’s schools, show it by investing in decent class sizes, supporting schools with adequate resources, and honouring the professional educators who daily commit to caring for young minds. Otherwise, we risk a pretend solution masquerading as a fix when in fact it may deepen cynicism, disengagement, and the degradation of public service.

You hold the power—and the responsibility—to choose how this chapter ends. I urge you to use that power wisely: with respect, with vision, with partnership—and with the long game in mind for public education in this province.

Sincerely,

Matthew Dance

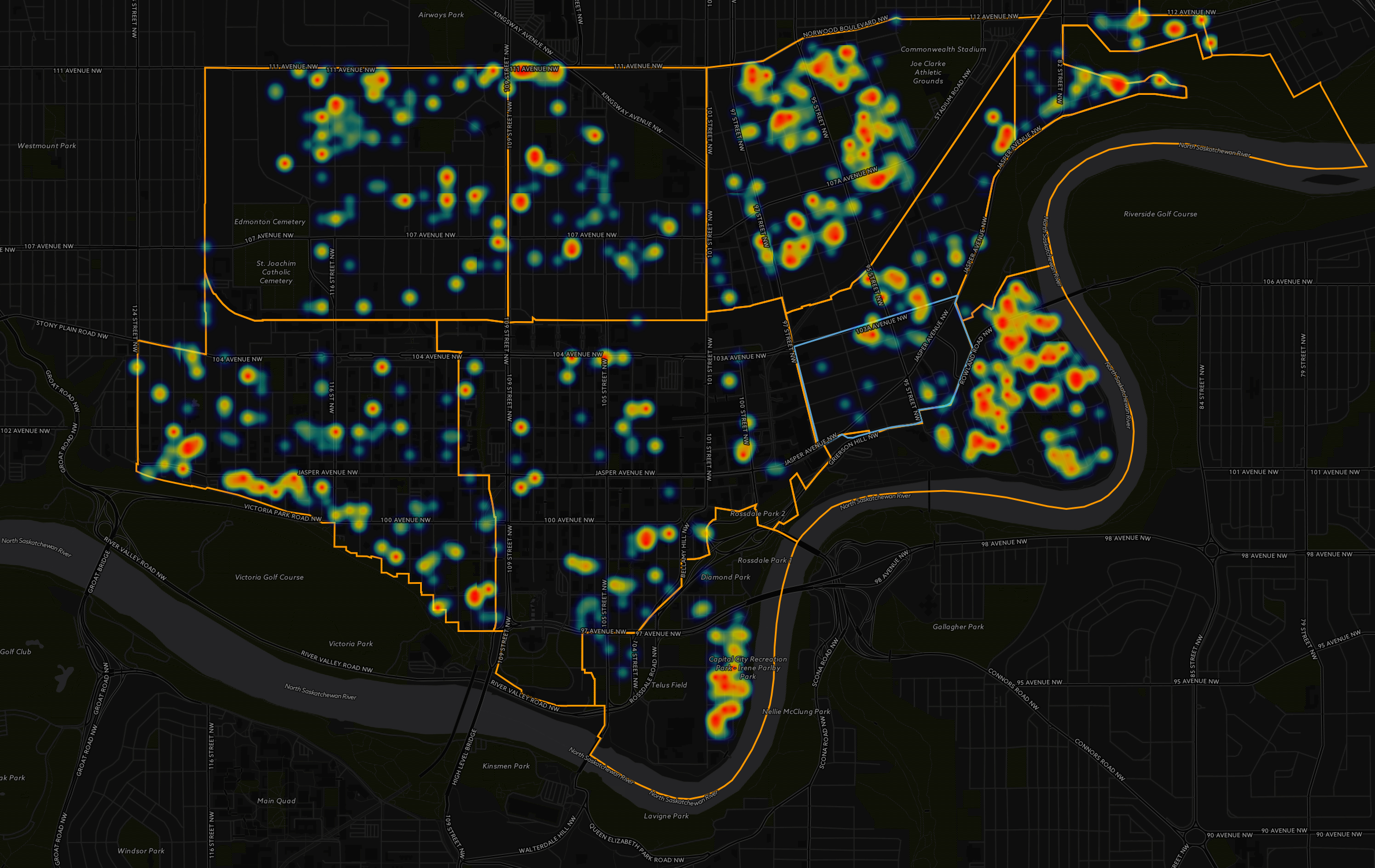

Edmonton Land Use: The Cost of Roads

“…if we think of space as that which allows movement, then place is pause; each pause in movement makes it possible for location to be transformed into place”

Tuan, 1977

Roads are a vital component to cities. They allow people to move through the city and also support the movement of goods and services. Roads are a vital part of the economy.

Roads are also a time and money suck, and in 2019 were directly or indirectly responsible for 14 deaths and 268 serious injuries[1]. Not to mention the GHG and other emissions that impact human health, climate and water systems.

Who benefits? Who benefits and what cost for Edmonton to maintain and actievly expand it’s extensive road network?

Let me tackle the cost item first. In the City of Edmonton’s 2020 Integrated Infrastructure Services Report Infrastructure State and Condition, Edmonton’s road network is valued at $9.6 Billion. That’s $9 614 000 000.

With reference to the map in the header, the specific costs to maintain / replace our road network are:

Arterial Roads, coloured black on the map. There are 3500 lane KM of arterial roads in Edmonton. The average age of arterial roads is 30 years, with an estimated asset life of 22 years, meaning that the average age of any section of arterial road is 8 years older than it’s estimated life. The replacement value for the arterial roads is $3.6 billion or over $1 million per lane KM.

Local Roads, coloured blue on the map. There are 4830 lane KM of local roads in Edmonton. The average age of local roads is 38 years, with an estimated asset life of 28 years, meaning that the average age of any section of local road is 10 years older than it’s estimated life. The replacement value for the local roads is $3.46 million or $716500 per lane KM.

Collector Roads, coloured orange on the map. There are 1763 lane KM of collector roads in Edmonton. The average age of collector roads is 35 years, with an estimated asset life of 20 years, meaning that the average age of any section of collector road is 15 years older than it’s estimated life. The replacement value for the collector roads is $1.9 million or $1 million per lane KM.

The cost of replacement does not include the cost of maintenance, such as snow clearing or filling potholes.

This ongoing expense is a liability, unless we can get it under control. We spend a lot of tax dollars on roads, and we are going to be spending a lot more as the gap between the average age of a roadway and its estimated lifespan increases. Also, we are expanding old roads, and building new ones with each new development that gets approved.

Roads account for 2/3 the total replacement value Edmonton’s people movement system. Light rail, transit and active movement account for just under 1/4. As the infrastructure report states, on page 19:

Overall, the average age of the Goods and People Movement Portfolio is 37 years with an expected life of 33 years. Roads’ assets are at or over their expected asset life. With appropriate maintenance and renewal schedules roads can be maintained past their expected asset life. However, there will come a point when full replacement will be needed.

As Brent Toderian said on Twitter: "The truth about a city's aspirations isn't found in its vision. It's found in its budget”. And it’s evident that Edmonton aspires to pay for roads into the future despite declaring a Climate Emergency, and implementing a Vision Zero program. To change this trajectory, Edmonton would have to buck the trend in not regulating roadways by:

More strictly regulating where and how new developments are built, and the mobility options made available.

Extend the life of our current roadway infrastructure (already being done through great maintenance) by providing options that will keep vehicles off the road. Active mobility such as bike lanes, expanding LRT and amazing bus service will all help.

Increasing density in the downtown and mature neighbourhoods will accomplish a few things. Greater density will bring more services within a shorter drive or even within biking and walking distance. Less driving, and other mobility options saves wear and tear on roadways, extending their life.

Who benefits from Edmonton’s roads? The ability to drive on Edmonton’s roadways is, at it’s core, an issue of class and race. Those who can afford a vehicle - who can afford all the daily/weekly/annual expenses such as gas, insurance, maintenance, etc. - have preferred access to mobility. Lower income folks, racialized and Indigenous people, older folks, non-drivers and children are all second class citizens in Edmonton. They all have barriers to accessing safe and affordable transportation that will take them where they want to go in a reasonable amount of time. In this sense, a just city that works for everyone is also a city that values it’s assets and is working to preserve the billions invested in roadways. It just makes sense, from a financial perspective, to invest more in creating a just city that values the transportation needs of all it’s citizens.

Notes:

From The City of Edmonton’s Vision Zero 2019 report, page 4.

Land Use in Edmonton: The Downtown Neighbourhoods

Figure 1: Parking, Vacant and Undeveloped Land in Edmonton’s core.

Land use can be defined as the management and modification of the natural environment to, in the case of Edmonton, create built or urban environments. Land use dovetails with zoning where a land use plan provides the big picture view of how a city can grow, and zoning provides a ‘block-by-block’ description of the rules used to manage the big picture. Within the context of Edmonton, both land use planning and zoning are settler-colonial constructs that entrench inequity within the fundamental building blocks of the city.

Within this context, I was interested in land that is “under utilized”[1] greyfield land across the downtown core. Some of the questions I am trying to tackle are: Is there a concentration of greyfield land? What communities surround it? Why is it under utilized? Is there a connection between land that is under utilized and zoning?

To do this, I created a land use map of Edmonton[2], and measured to footprint area of land classified as parking, vacant and undeveloped within the 8 neighborhoods that make up the downtown core of Edmonton. From west to east, those neighborhoods are Westmount, Oliver, Queen Mary Park, Downtown, Rossdale, Central McDougall, McCauley and Boyle Street.

What is the extent of underutilized land in Edmonton’s downtown core?

Figure 2 (below) shows the areas of the downtown neighbourhoods that are occupied by parking, undeveloped and vacant land[3]. I’ve grouped all parking polygons (surface paved and surface gravel, parking structures, etc) in the land use data set as parking and I am only considering their footprints. I am also only considering the footprints for vacant and undeveloped land. Finally, the polygons in Figure 1 (in the header) directly correspond to the land cover percentages in Figure 2. Looking at the map, we can see that all of the 8 neighbourhoods have some portion of their area relegated as parking, vacant, and undeveloped, and the graph defines the percentage of land cover for each parameter.

Figure 2: Parking, Undeveloped and Vacant land in Edmonton’s downtown neighborhoods.

What’s going on here?

I was surprised by the variety of zoning in Westmount and Queen Mary Park (QMP). Single family detached, direct development control (I’ll get back to this) and small scale infill define the larger blocks, with some business and other zoning rounding out the neighbourhoods. There is not a lot of surface parking lots in either neighbourhood, and less than 2% of other land use is vacant or undeveloped.

Central McDougal has a variety of land uses from the Royal Alex Hospital in the N.E, to the Victoria School of the Arts and Boyle Street Community Services and some amount of parking desert in the S.E., behind rogers Place[4]. The parking associated with the Alex, down 101 Street and behind Roger’s Place accounts for the majority of the 5% parking allocated to land use. There is a small about of vacant land and undeveloped land the looks to be waiting for development. The neighbourhood is underlain by zoning that supports low and medium rise apartments, urban services and low intensity commercial development, and direct development control provisions.

Downtown also has a variety of land uses from Grant MacEwan and the RAM in the north, to the Legislature to the south. Almost 7% of the land area downtown is devoted to parking. Please note that I’ve only considered parking foot prints. I’ve not included parking that is under commercial buildings - for instance Commerce Place. I have included the footprint of multi level parkades. There is a not a lot of vacant or undeveloped land. Of the ~7% of land covered by parking, some is associated with the ‘business’ area. There is a cluster of parking in the ‘Warehouse Zone’ between 109 and 105 Streets, north of Jasper. Many of these will be removed with the great development of the Warehouse Campus Neighbourhood Park.

McCauley is a very eclectic community, with “Church Street”, as the cluster of churches along 96th Street is called, the North portion of Chinatown, Little Italy, and a number of railways as will as residential and business zoning. Considering all the business located in Chinatown and Little Italy, the amount of land devoted to parking is around 3%, and there is a small portion of undeveloped and vacant land.

The remaining neighbourhood, Boyle Street, is unique in an Edmonton context. Over 16% of Boyle Street is covered by greenfield, and of that almost 8% is surface parking. As such, I will discuss Boyle Street in my next post.

Conclusions

I find the language used and the act of land classification to be cold and transactional, removed from the connection, the emotional value and health we derive from land. It’s like the values we espouse as a city related to place making, reconciliation and being in the midst of a climate crisis are divorced from the transactional way we settlers use and value unceded, stolen Indigenous land.

Not included in the Land Use data is transportation infrastructure, despite the fact that it will occupy, as a rough calculation, up to a third of the land use in Edmonton with the blacktop alone being valued at $9 billion[5]. I will examine transportation infrastructure in more detail in an upcoming blog post.

While I have not done the math (yet) on this, it seems that there is a correlation between “Direct Development Control” zoning and a prevalence of surface parking lots (see below). I will get into this in more detail in my next post on Boyle Street.

In the beginning I asked “Is there a concentration of greyfield land? What communities surround it? Why is it under utilized? Is there a connection between land that is under utilized and zoning?” Generally, I don’t think that there is a strong correlation between zoning in the downtown neighbourhoods and greyfield land. Unless you happen to live in Boyle Street. I will get to that more complete and complex analysis in next time.

Finally, I did not consider gender, class or race in relation to greenfield land use and zoning. These are huge issues that should be treated with robust analysis and great sensitivity. I am still trying to understand how to adequately do this.

Blue represents Direct Development Control zoning, grey represents parking and black represents vacant land.

1 - “Greenfield” is used to generally describe the land that is classified as ‘parking’, ‘vacant’, and ‘derelict’. I found it extremely challenging to write about land without any value judgements. I think the language we use - “development”, “greyfield”, “greenfield”, and I have not succeeded in this, and I understand that different communities may view a parking lot, for example, as a gathering place that is relatively safe and away from the scrutiny of security that “protects” both public and private land in Edmonton.

2 - The datasets I used for this mapping project are: Land Use, Neighbourhood Boundaries, Zoning, and the road network. I created the maps in QGIS3.10.12, and used Open Street Map as a base map for reference.

3 - “Parking” can be defined as an area designated as a parking lot that charges a fee to park. I did not consider on-road parking. I am not sure of the distinction between “vacant” and “undeveloped”.

4 - Rylan Kafara, a University of Alberta PhD Student, wrote a great paper on the stigma faced by people experiencing homelessness proximal to Roger’s Place: Sociology of Sport Journal - Negotiating the New Urban Sporting Territory: Policing, Settler Colonialism, and Edmonton’s Ice District.

5 - From the City of Edmonton’s Integrated Infrastructure Services 2020 Infrastructure State and Condition report, page 31, Appendix A - Inventory, State & Condition and Replacement Value,

What is Zoning?

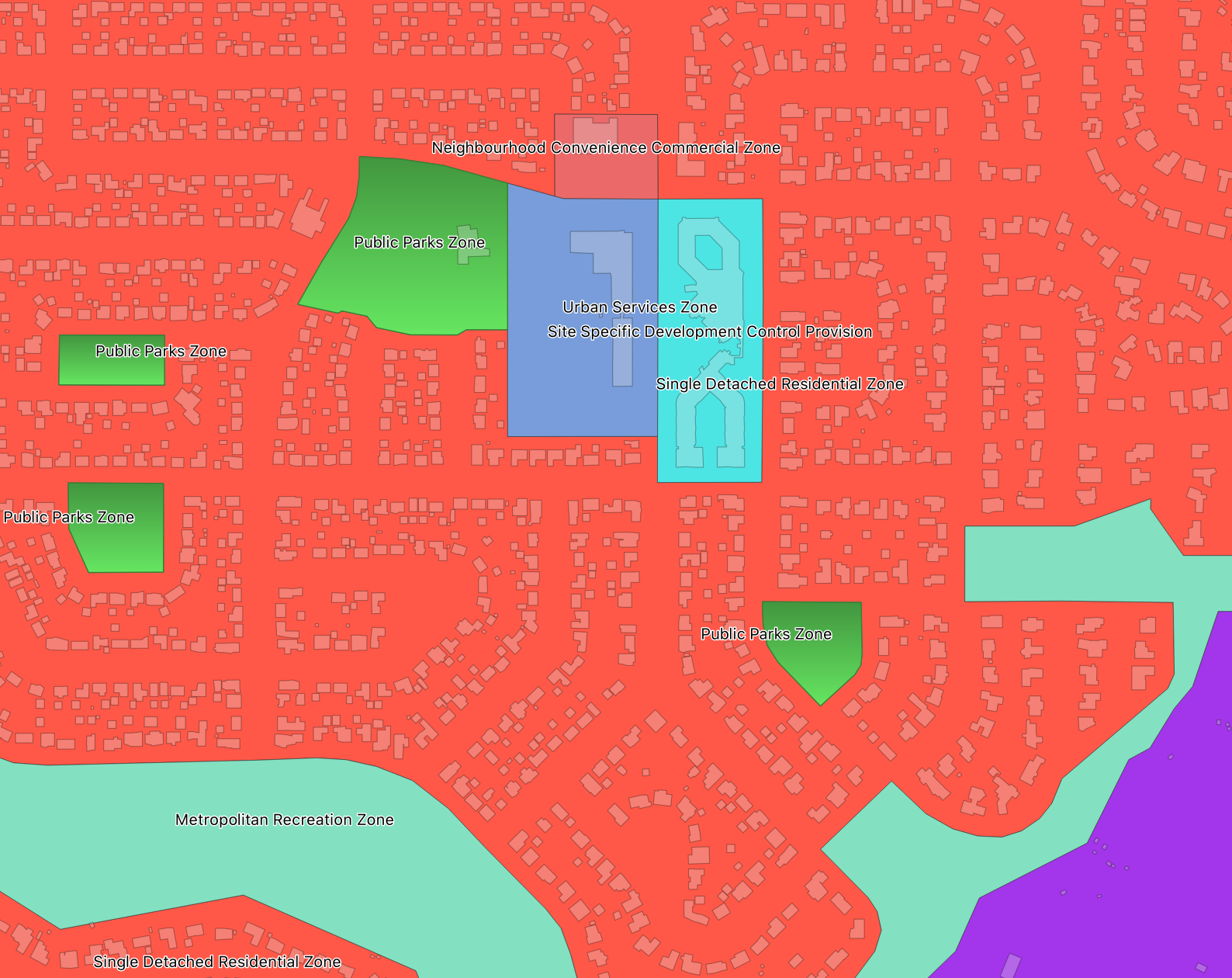

A colourful rendition of Edmonton’s Land Use Zones - Downtown and surrounding neighbourhoods. Created in QGIS using zoning data from www.data.edmonton.ca

What is zoning? I mean, besides that thing you do, during a pandemic, when the T.V. is on.

Zoning, as defined by The City of Edmonton in ‘What is Zoning? How it Shapes Your Neighbourhood and City’, “…allows City Council to set rules for where new buildings should go, what types of buildings they can be, what activities and businesses can happen there, as well as requirements for other things such as landscaping.” (pp. 4). The What is Zoning document goes on to describe the relationship between zoning and land use planning: “Zoning is the legal tool that ensures that the buildings that are built support the vision in the Land Use Plan.” (pp.11).

Zoning creates ‘zones’ or areas within a city to manage land use within that area, and avoid conflicts between conflicting land uses. For instance, there is a zone for single family homes called ‘Single Detached Residential Zone (RF1)’ which stipulates all the rules for building a single family detached home in that zone. There is also a zone for ‘Public Parks (AP)’ and for ‘Neighbourhood Convenience Commercial Zone (CNC)’. These three zones work well together because it’s desirable to have parks and conveniences such as a corner store or cafe adjacent to your home. It’s not desirable, on the other hand, to have a light industrial development, manufacturing or highway next to your home (and I will get to this exact issue in a future blog post).

And all of these zone types - and associated rules and policy - are described in the Zoning Bylaw. For example, the Neighbourhood Convenience Commercial Zone is described as:

The purpose of this Zone is to provide for convenience commercial and personal service uses, which are intended to serve the day-to-day needs of residents within residential neighbourhoods.

What does this look like on the ground (or on a map….)?

Zoning in the Laurier Heights and surrounding areas. The orange represents a ‘Single Detached Residential Zone’, the green represents ‘Public Parks Zone’, the darker blue represents an ‘Urban Services Zone’ (Laurier Heights School), and the light blue represents a ‘Site Specific Development Control Provision’ (The Canterbury Court retirement community). The ‘Metropolitan Recreation Zone’ is a wide ranging zone used though much of the river valley; the section shown in the image above also has the section of the Whitemud north of the Quesnell Bridge. The purple zone contains the Valley Zoo, and is called a ‘River Valley Activity Node.’

Created in QGIS using zoning data, neighbourhood and roof line polygons from data.edmonton.ca.

Simple, right?

Not so much.

In taking a critical view of zoning, it’s possible to ask some questions that shed a light on who zoning serves, who the decision makers are, and who benefits as zoning carries with it deep seated inequity. What do I mean by inequity? If zoning simply defines what types of buildings can be built where, how does that create inequity?

In a general sense, the act of deciding what can be build where will invariably include some folks in the most desirable locations, and exclude other people from those same locations. For example, a casual examination seems to indicate that the most dominant zone adjacent to Edmonton’s river valley is the ‘Single Detached Residential Zone’. It makes sense, right? Build single family houses close to amenities like the river valley. Only, this would be inequitable if only wealthy people can afford to live in the houses built in neighbourhoods adjacent to the river valley.

The same is true for access to other services like other green space, supermarkets, hospitals, etc. On the flip side, we can ask who lives next to our busiest roadways? Who lives closest to the refineries on the east end of Edmonton? Who has access to quality transit? Who lives in food deserts?

I hope to look at these questions in the coming weeks using the data found in the City of Edmonton’s open data portal. I will explicitly link to the data and tools I use, and analysis I conduct.

Caveat time: I am not an expert in zoning and land use planning. I am a white CIS male heterosexual and am one of the people who benefits from zoning. That said, I hope to bring something to the zoning discussion by looking at zoning through a lens of equity and white supremacy, and am happy to have my work reviewed and critiqued.

This blogging project is intended as a way for me learn about and explore zoning in Edmonton, to pull in examples from other jurisdictions, and act as a tool to document and explain my learning.

Please let me know what you think.

Data Sources:

The Zoning Map Data is on data.edmonton.ca and can be found here.

The Zoning Bylaw can be found here.

I use a free and open Geographic Information System called QGIS. It is available for Mac, Windows and Linux operating systems and can be found here. If you are interested in GIS, this is a great place to start as QGIS is easy to download and install on your computer, and the project supports a ton of instructional material through the website, and on other channels such as YouTube and StackOverflow.

Rockwall Trail Report

Rockwall Trail - Field Notes

The Rockwall Trail is a 54 km backpacking trail in Kootaney National Park (Kootany is an anglicized name from the Ktunaxa people, which means 'people from beyond the hills'(1))) that runs roughly parallel to- and on the west side of- Highway 93. The 93 was, in part, what motivated my desire to hike to RW. I've driven this road a number of times, summer and winter, and have gotten tantalizing glimpses of the mountains from the highway. The highway is a beautiful and remote feeling, especially in winter and encapsulates a lot of what I love about the East Kootaneys.

I had originally booked 4 nights and 5 days to hike the trail, meaning that our longest day would be 15km, and the typical day would see us walk only ~10km. But, I messed up the booking, and could only get Flow Lake on one night in July, and the campsite 10km before Floe Lake was not free the night before. So, 3 nights, 4 days and a 20km leg. Right.

Day 1, Paint Pots to Helmet Falls

Depart 13:40

Arrive 18:50

14.9KM, 310m of elevation.

We started on a busy afternoon, parking at the trail head full of typical summer traffic - large camper vans and RVs and many cars from many places including Alberta and BC (of course), but also Oregon, Washington and from out east.

Erica and I take a few minutes to organize our bags and to leash up the dog. I shoulder my pack - I had forgotten how heavy 45lbs felt - and after a pause for a selfie, we head out. The trail up to the Paint Pots is pretty busy with all the drivers of those cars, and the Paint Pots themselves are interesting. But we don't pause for long as it's already late in the afternoon and we have some miles to walk.

It's a long day of steady but easy hiking with some minor steeps and continuous elevation gain amounting to 310m over the 15km. The reward at the end of the day is a lovely river crossing on a suspension bridge (we stopped for a brief bite and to fill up or water bladders at the river’s edge) followed by views of Helmet Falls, The Rockwall, and the cute Warden's Cabin.

Day 2, Helmet Falls to Numa Creek

Depart 09:25

Arrive 19:45

19.4KM, 1050m of elevation

This was a gruelling day that tested our endurance.

After a breakfast of homemade oatmeal packed with with dried fruit, coffee and chocolate (I love backpack for the simple fact that I eat chocolate for breakfast, guilt free), we started hiking up the valley to unimpeded views of Helmet Falls. The views of the falls would foreshadow the rest of our day as we would go over two mountain passes and spend some time in the high alpine.

We gained some elevation and walked under Limestone Peak (288m) that was hidden in the clouds. Most of the Washmawapta Glacier, just south of Limestone Peak was also hidden from view, with the exception of a smaller portion of the glacier that lay at the foot of the wall. Washmawapta means 'ice river' from language of the Stoney Indians.

In addition to grand views, the ascent up to Rockwall Pass also brought rain, mud and large pockets of remnant snow, but we were prepared with short gators and hiking polls. It was exhilarating to be tracking across the high plateau through knee deep snow and across streams, through the mud with the Rockwall ever present to our right. The high alpine snow was fascinating. Textured and multicoloured, streaked with watermelon pink from algae living in the snow.

We keep to the left at the Y in the trail, heading towards Tumbling Creek and away from Wolverine Pass. After another long traverse across Wolverine Pass Trail, exposed and vulnerable to the elements, we descend from the snow, the trail orange-brown and sinuous through the grass and trees. Hungry and a little over extended we arrive at the Tumbling Creek Campsite and stop briefly to eat Montreal Bagels, PB&J, and the last of the beef salami and cheese. I was happy to eat, as each mouthful lightened the load in my pack.

We proceeded to the second and shorter leg of the day, up and over Tumbling Pass to Numa Creek Campsite. Numa is a Cree word for thunder, and Numa Peak was once called Roaring Mountain. Tumbling Pass offered similar views of the Rockwall, but wetter! Tumbling Glacier and Peak and Hewitt Peak (both over 3000m) loomed over us, and a vast limestone face paralleled the descent, huge and glowing in the wet sunlight. We paused and watched the rain move up the valley from the northeast as a rainbow made a brief appearance between the clouds and mountains.

The switchbacks down to the Numa Creek Campsite were treacherous and cut by many streams that were easy to cross, and one that took some effort. There was no bridge across the steep and swollen creek with sketchy rocks and cold fast flowing water, our feet got wet and it could have easily been much worse!

Erica and I were getting tired when we entered the endless mud luge narrow, steep and slick trails descending tight through tall and wet vegetation. We paused often hollering for bears, passing a sign saying 2.5km to the campsite and then proceeded to walk what felt like 10k.

Finally, after 10 hours and 20 kms we got to Numa Creek. Dinner was quick, sleep was deep.

Day 3, Numa Creek to Floe Lake

Depart 10:20

Arrive 15:40

10.0KM, 830m of elevation

The approach to Numa Pass is surprising in it's steepness and quick ascent up the headwall. Starting gently as the trail follows the upper reaches of Numa Creek, we have great views of waterfalls and mountains to the southwest (always with the views). Pausing briefly for some snacks, we start up the steeps.

We emerge onto a sloped Tamarack Forest, snow dappled with fallen needles from last autumn, and we continue upward. More snow lay in the most shaded areas, with mud covering the trail, simple in it’s beauty of muted browns, green and white. Finally, we break through the tree line and watch as another couple traverse the northern slopes of Numa Pass, moving from scree to snow and back again, up and over.

We follow their footsteps, pausing to look back to the northwest as we gain elevation. Finally, just after 13:00, we crest the pass (formed between Numa Mountain (2487m) to the northwest and Foster Peak (3201) to the southeast) and have our first glimpse of Floe Lake and Floe Peak (3006m). We also note, with joy, that we've completed all of our significant elevation - it's literally all downhill from here.

On the lee of the pass we see willow leaves littering the snow, likely blown over the pass by an anabatic wind from the northwest, flowing up and over much more easily than us.

Down down through tamarack, then spruce and pine to Floe Lake. It's early, so we set up camp, introduce our dog to the other camp mutts, and sit lakeside watching the light play across the glaciers, rocks and water of Flow Lake.

The shifting light on the gentle arc of a terminal moraine is magical. One minute backlit by sun on snow, the next front lit as the sun and clouds shift, moving the intensity of the light to the lake. This plus a million variations as the sun arcs west and the clouds shift on the wind to the south, opening and closing like blinds letting in the light.

Day 4, Floe Lake to Floe Lake Trailhead

Depart 10:40

Arrive 14:40

10.5KM, 715m descent

We linger at Floe Lake, drinking coffee and packing slowly. It's sunny and lovely and we are (in part) still tired from the previous days hiking and (in part) taken by the beauty and majesty of Floe Lake.

We finally get on the road by 10:40, and are immediately going down, descending thought forested switchbacks that quickly turn to the recovering remains of the Verendrye Creek Fire of 2003. The fire section is exposed and hot, with little access to water. The hike turns from a pleasant walk through flowers and berries (eek, bears!) to a bit of a slog.

We finally level out and cross Floe Creek once, and then again about 1000m later. This final stretch seems to take forever, we are hot and tired, but about 500m later we emerge the trailhead on HWY 93. Friends we met on the trail shuttle me to the minivan parked 16km away at Paint Pots. The drive to pick up Erica feels luxurious, my boots replaced by Birks, the windows rolled down and the cool wind drying my sweat stained t-shirt. We stop at McDonalds on the way back to civilisation, and I eat one of my top 5 meals of the year consisting of a Big Mac, Fries and Coke with lots of ice.

Total Tally: 4 days, 54.4 KM and over 2100m of up.

Final thoughts

All place name information I found on the Kootany National Park website.

I was hoping to discuss the glacial history of the Rockwall Trail, but I couldn’t find detailed historic or current data that was specifically about this area. I can say (from The Quaternary Geologic History of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, Bobrowsky and Rutter, 1992) that during the Pleistocene glaciers filled these valleys, but were originated locally. They retreated about 13000 years ago, leaving remnant glaciers that can be seen along the hike (there are 8 of these that are in the mountains west of the trail), and I referenced and photographed some of them. We crossed many locally created glacial features as well, most notably be hiked across and up a terminal moraine and lateral moraine.

Glaciers, and their landforms, have always been an interest of mine, and I fear that my kids will never have the same opportunities as me, opportunities this hike afforded to see glaciers in person.

Edmonton Parking Map

Project Scope

To map all of land space occupied by parking lots within the ring road in Edmonton.

Goal

To map the 2 dimensional land space (x- and y- coordinates resulting in a polygon) occupied by ground level and multi-level parking within Edmonton's ring road.

- All surface lots will be mapped.

- The surface area of all multi-story parking lots will also be mapped.

Outcome

An accurate calculation of the land area occupied by parking structures within the ring road in Edmonton. This calculation will reflect the total land area or the percentage land area within the ring road. The type of parking lot will also be documented (surface, multi-story; gravel, paved).

Process

- Please sign-up here for mapping a section of Edmonton. The sign-up is based on the 12 Wards of Edmonton. A detailed Edmonton Ward map can be downloaded here.

- Open OpenStreetMap.org. If you've not registered on OSM, please do so as you will need to log-in to edit the map.

- Once logged in, you can access the iD editor, OSM's embedded map editor. If needed, have a look at an OSM iD Editor tutorial here.

- Edit away.

- Add parking polygons, and;

- Add metadata in the table to the edits. It's easiest to search for 'parking' and then fill in the drop down menu. If know, please add data to 'name', 'type', 'capacity', and 'surface' (please see below).

- As you complete each Ward, please indicate on the signup sheet that status.

- Tweet your edits as well, and remember to tag me @mattdance for RTs.

- Once all of the parking is mapped, I will download the parking data and convert to a SHP and GeoJson files and post on my blog for people to use. I will also submit to the City of Edmonton Open Data Team to see if they'll post to the City's open data portal.

- Finally, if you have any issues or concerns, please let me know @mattdance #yegparking.

Thank you!

Actually, it's Staples that's flawed

I wrote this piece on April 25th and submitted to the Edmonton Journal as a rebuttal to David Staples column mentioned below. On April 28th I left for some vacation. On May 15th I reached out to Bill Mah, the Journal's OpEd Editor, asking him if I could post to by blog, he replied: "Yes, please do so. We weren’t able to get to it.".

Forty kilometre-per-hour residential speed limits are totally safe — unless you're young, old, or hit by anything other than the driver of a car.

On April 25, David Staples argued in a column (“City officials relying on flawed data in push for 30 km/h speed limit”) that a 40km/h residential speed limit is a reasonable compromise between the current limit of 50km/h and the position that many advocates are pushing for —30km/h.

In this column, Staples cited two research papers to bolster this argument*. He also cherry-picked his quotes to advance his position. As a result, I have a few criticisms of his logic and conclusion. Both, to borrow his term, are flawed.

Now, to be clear, I’m advocating for a residential speed-limit policy that protects the most people in most circumstances. And I also support the development of a multimodal transportation network that includes vehicles such as cars, vans and trucks.

This point, that advocates are not against cars, is being lost in the current debate.

But let’s get to it. Here’s what Staples got wrong: while he quoted a French study, he took the quote out of its context (isn’t avoiding that rule number one for journalists?) and thus changed its meaning.

Staples’ quote: “For speeds less than 40 km/h, because data representative of all crashes resulting in injury were used, the estimated risk of death was fairly low.”

This implies the risk of death would be low if Edmonton were to implement a 40km/h limit.

But, Staples omitted the line that follows: "However, although the curve seemed deceptively flat below 50 km/h, the risk of death in fact rose 2-fold between 30 and 40 km/h and 6-fold between 30 and 50 km/h."

This changes the meaning. Instead, this quote now indicates that the risk of death for a pedestrian is doubled between 30 and 40 km/h.

And for Staples’ credibility, it only gets worse.

The French study showed that, compared to the age group of 15- to 59-year olds, being older decreases your odds of surviving a collision with a vehicle. For those older and frailer, the study found fatality was significantly higher with speeds as low as 30km/h. For those between 60 and 74, however, the risk of death increases two-fold. For those over 75, there is a seven-fold increase. In addition, being struck by the driver of a van or other utility vehicles increases mortality risk, as does being struck by the driver of a truck — there, the risk increases by an astonishing 14 times.

The French study also found the risk of a pedestrian being killed is also greater at night, as well as when crossing outside of a marked crosswalk.

The French study Staples misused also goes on to put these statistics into a policy context. The authors indicate that those jurisdictions promoting walking and cycling (like Edmonton) might be increasing overall road traffic injuries unless appropriate strategies, such as speed management, are put into place. They suggest, among other things, “reducing vehicle speed, [and] separating pedestrians from other road users.”

The authors conclude by stating, "The present results confirm that when a pedestrian is struck by a car, impact speed is a major risk factor, thus providing a supplementary argument for strict speed limitation in areas where pedestrians are highly exposed."

A close reading of the paper that Staples cites to claim the city’s data is “flawed” actually provides ample evidence that it’s his conclusions that are. In fact, its authors argue for “strict speed limitation in areas where pedestrians are highly exposed.”

Still, why 30km/h instead of 40km/h? Why is one better than the other?

While an adult person might not be killed by the driver of a car going 40km/h, a younger or older person probably would be. For me, that’s not good enough.

I want the streets of my city to be safe for old and young people to walk and cycle. I want people to be safe from trucks and vans, too, and not just cars. And that demands that we define “strict speed limitations” on residential roads, where people walk and bike and exist in their neighbourhoods. That speed limitation should be 30km/h for residential roads.

I’m encouraged that Edmonton is moving in the right direction. Almost no one in Edmonton is advocating for the status quo.

Except City Council.

Columns that rely on sleight of hand and flawed methods to reach flawed conclusions certainly don’t help make our city safer.

Air Quality and Asthma

In 2007 I took a GIS course prior to starting my MA - I was interested to see if I could do school again having graduated from my BA in 1995.

The final paper from that course took a GIS approach to look at the correlation between air quality and asthma. Please see below for the Executive Summary and a link to download the paper if you are interested.

“Executive Summary

It is well understood that there is a positive association between air pollution and emergency department visits for asthma in Alberta (Rowe pers. comm.). Within this context, we explored the correlation between air quality, as measured by ambient and point source parameters, and asthma related ED visit rates in Alberta. We tested the following four hypotheses:

H1: As the proximity to point sources increases, the instance of asthma increases.

H2: As ambient air quality decreases, the instance of asthma increases.

H3: Urban areas will have poorer ambient air quality than rural areas.

H4: Urban areas will have a higher rate of asthma than rural areas.”

4 Things the Government of Alberta Could Do To Advance Open Data

Recently, the Government of Alberta posted for the position of Chief Officer, Digital Innovation Office. The opening paragraph of that job posting reads:

The Government of Alberta is embarking on transforming the work of government to deliver simpler, efficient, and better services for the citizens of Alberta in the digital age. A dedicated office, led by the Chief Officer, will be established to drive digital innovation across government. The Digital Innovation Office will be composed of a small team of progressive thinkers, innovative technologists and creative disrupters who provide a government-wide lens on the problems at hand and a society-wide lens on the solutions available.

The full posting can be found here.

This is a big and important position that, if filled by the right person and with the appropriate support from within the GoA, has the potential to change how the GoA manages data and engages with citizens.

In the mean time, though, I have 4 suggestions on how the GoA can embark "...on transforming the work of government to deliver simpler, efficient, and better services for the citizens of Alberta in the digital age." These suggestions build upon the existing infrastructure and deep knowledge within the GoA's open data / open government teas.

1. Create an open data portal that only hosts open data.

I will be the first to admit that I can, occasionally, be a little too focused on process and names. I like to call things what they are. As such, it seems that if a government is hosting an open data portal, that portal should contain exclusively open data, because it's an open data portal. The GoA open data portal currently hosts both open data and PDF reports (PDF is not an open format as it can't be used or manipulated that way a CSV file can). When I posed the question to the Government of Alberta Open Data Team (@OpenGovAB) via Twitter, they did clarify that:

we are one of the few #opengov portals that posts #govpubs as well as #opendata. bit.ly/2Ho4Z9e is found under the Publications section, not the Open Data section. We do distinguish between the two.

There is a great deal of ambiguity between the 'open' section of the portal and the 'publications' section of the portal. Specifically, the URL prefix of 'open.alberta.ca' that signifies that I have navigated to the open portion of the website is also the prefix to the publications section of the portal. The fact that the publications section reads 'open.alberta.ca/publications' implies to me that these are open publications; publications posted in a machine readable or some other open platform.

But they are PDF's.

Hosted on an open data portal.

The solution is to simply change the URL for the publications section to 'publications.alberta.ca'.

Problem solved.

2. Aggregate all of the Government of Alberta's open data products onto open.alberta.ca

Off the top of my head I can point to four locations where the GoA hosts data available to the public (and there may be many more):

- Historical air quality is hosted at 'airdata.alberta.ca' and cannot be found with a search at the GoA open data portal and 'airdata.alberta.ca' does not use open data standards to access the dataset. In fact, you must access the data via drop down menus (the most frustrating way to access data, even more frustrating than a PDF).

- Many spatial datasets are hosted at AltaLis, which states that they are working towards becoming a "‘One Stop Shop’ for data in Alberta." There seems to be a conflict here. Is AltaLis the Government of Alberta's open data portal, or is 'open.alberta.ca'?

- The Oil Sands Monitoring Portal (OSIP) which provides "... the public with information about the impact of the oil sands on Alberta's land, water, air, climate, and biodiversity." The OSIP is difficult to use and contains many different types of data, and has yet another type of data interface design.

- Finally, The GoA Open Data Portal.

The problem with this arrangement is threefold:

- There are three different UX/UI interfaces that mediate the access to these three different sites.

- There are three different data license agreements applied to these three sets of data.

- There are two different costs to these data - a large number of the AltaLis datasets are for sale, even though they are collected for the province (i.e. paid for by tax payers).

- The GoA places closed data in the form of PDFs on the open data portal when there are clearly other 'open' datasets that are available in other section of the GoA website. These datasets (like the oil sands monitoring data and the historic air quality data) should be searchable via the open data portal.

This makes the GoA open data confusing and ambitious. Where do you look for a specific dataset? Will it cost money to use? Under which license can I use it?

The solution is to standardize everything, and then get out of the way.

Standardize the internal process for releasing data.

Standardize the license agreement.

Standardize the cost as free.

Standardize the UI.

Standardize the location of open data on the open data portal, and only host open data at that site.

3. Post more open data

Finally, the GoA should post more data to the open data portal. I wrote an OpEd in the Edmonton Journal on why the GoA should post the traffic collision dataset to the open data portal. The arguments that I made in that article can be generalized. As the GoA acknowledges, open data drives innovation. It doesn't matter if you are an entrepreneur or simply an engaged citizen with an idea or passion, open data provides a venue to explore ideas that can change how cities or provinces work. It was open data that laid the foundation of Edmonton's minimum bike grid. These Planning students are using open data to explore Edmonton's neighbourhoods. The possibilities are only limited by the data posted by our governments.

So, stop limiting the data.

Conclusion

While it's clear that the Government of Alberta is interested in becoming a leader in digital information and services, it's unfortunate that they feel a need to create an entire Digital Innovation Office to do this. The GoA is missing the most basic open data steps of creating machine readable data that are easy to find and exist within a permissive legal framework.

Unfortunately, this lack of attention leads me to believe that Alberta will remain a digital provincial backwater until the time when the GoA takes their open data platform seriously.

Naming Edmonton: A Method for Classifying Edmonton Place Names

Update

We have geo-coded all of the names in the dataset! Thank-you to those who have contributed time and effort to make that happen!

Background

One of my desired outcomes in the Naming Edmonton Project is to classify all of Edmonton's place names based on origin (i.e. where did the name come from) and gender (if applicable). My hypothesis is that the vast majority of Edmonton's place names are British and if gendered, are male. I'd like to test that hypothesis and quantify the numbers; (1) the percentage of place names from the UK as compared to other locations, and; (2) the number of places that are named with a person's name, and the gender of that name.

But to test this hypothesis, I need a Naming Edmonton dataset that has been classified. And this is where you come in. I have developed the following method for name classification after consulting some naming literature and talking with Alberta's Geographical Names Program and an urban geography professor at the University of Alberta (Dr. Damian Collins). The intent of this method is to be rigorous so that we can create a defensible dataset.

What to do?

The Classifications

The place name is to be classified into 3 categories:

1. Name Origin (from Alberta Geographical Names Program):

Name Origins can be one of these:

Commemorative (A name, such as Alexander Thiele Park; or a feature such as a Castle in Castle Downs)

Land Feature

Botanical (i.e. Wolf Willow or Aldergrove)

Royal (Kingsway, Queen Alexander, Alberta)

Other or Unknown

The name origins are usually found in the description of the place, for instance, "Alexander Harold Thiele (1920-1981) was an Edmonton lawyer ...".

2. Cultural Affiliation: Where did the feature or name from 1. above come from? This is the complicated part. I address how to check for cultural affiliation in the method below.

3. Gender: Gender can be defined as Male, Male and Female, Female or N/A. I describe how to assess this in the method below.

The Method (I have an example below)

1. You will need spreadsheet software to work on this - Excel, Numbers, etc.

Please download a 'letter' from here - be sure to check the comments below to make sure you are not duplicating someone else's work (I have removed all data from these spreadsheets except the place name and description- don't worry, the geocoding has been saved). Please leave a comment below that you have downloaded and are working on that letter as we don't need to duplicate the effort.

2. Have a look in the description. Please look for clues or an explicit statement as to the name origin. Fill out the Name Origins column based on the details found in the description. Please also correct any spelling mistakes.

3. Look up the Edmonton place name in the Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names (here). Not all names can be found here, and if not Google the name such as 'Thiele Surname Origins', or ' Thiele Surname Origins Wiki'. From that determine where the name originated and fill in the 'Cultural Affiliation' column. For instance, the surname of Thiele is German, so the 'Cultural Affiliation' is German.

4. If it's a botanical or land feature name (i.e. Forest Heights or Wolf Willow), not found in the Oxford, attribute it to Canada - local flora, fauna, or land feature.

5. If it is a FNMI name that has been transliterated to English, such as Blue Quill, indicate the 'Cultural Affiliation' as FN.

6. Google it to see if there are any hits. For instance, Quesnel - I thought was a FNMI name is actually the name of a French explorer born in Montreal, after his father (Joseph) who was born in France. 'Cultural Affiliation' would then be French.

7. Finally, if the named place is a proper person's name, document the 'Gender' in the appropriate column. For the gender, please indicate one of the following: Male; Female; Male and Female; Not Applicable (N/A).

8. Save your work and email the document to me - matt@matthewdance.ca.

Please don't worry that you will make a mistake, just highlight the problem name and leave a note describing the problem in an adjacent cell. I will be double checking all of the data input to the spreadsheet. Thank you!

Sample

Web mapping tools - from beginner to advanced.

How do you make a web map?

This post comprises a list of my mapping tools beyond those discussed in the Naming Edmonton events. For some more detail on the geographic concepts relative to map making, please see mapschool.

Data Sources

Open Data (definition)- Open data forms the basis for most of my base map data, my goto data portals are:

- Edmonton's Open Data Portal

- Geogratis

- Government of Alberta's Open Data Portal

- Government of Canada Open Data Portal

- Stats Can

- Natural Earth

- Open Street Map Metro Extracts

- Open Street Map Country and Province Extracts

- Canadian GIS: a list a open/free data sources from Canadian GIS

- A GIANT LIST OF OPEN DATA REPOSITORIES (Really. It's giant.)

I mix and match the data found in these portals to try and make maps and do analysis that provide insight into questions of urban form and geography. When combined with one or more of the following GIS tools (GIS definition), open data can provide some pretty cool insight.

Desktop GIS

Cartographica - I mainly use Cartographica as a desktop geocoder and quick & dirty data viz tool. I love how simple it is to dump data into the view window, and how quick it renders large data sets. It is a light and easy way to quickly get a sense of a dataset, plus it has a 'live' map feed of OpenStreetMap or Bing. It can import or export to KML, and complete some lightweight data analysis like heat maps. Unfortunately, you have to purchase this software.

QGIS - Where Cartographica is light and costs, QGIS is robust and free. It is a full GIS on your desktop, and because I run an iMac, the easiest way to do spatial analysis without loading a Windows VM for ArcGIS (and much cheaper too, as in free). I love QGIS, but it requires a set of skills comparable to those used in ArcGIS and will require some effort to learn.

Web Based GIS

MapBox - MapBox provides three services that I find vital - (1) web hosting, (2) base maps that can be styled, and (3) MapBox Studio which allows the user to build beautiful custom maps with imported data. Also, MapBox provides some great satellite imagery as a base map, and an awesome blog on what is new in mapping. It is more complicated to learn than CartoDB, but provides greater flexibility once you acquire the skills.

CartoDB - Perhaps the most straightforward web tool to use, CartoDB allows the user to simply import data, view the table or map, and then style the data. Many layers can be added, and simple analysis / visualizations can also be run. There are also a selection of base maps to choose from. I love how CartoDB makes temporal data come alive. Check out this map of '7 Years of Tornado Data', and how you can almost pick out the season by the amount of tornado activity.

Additional resources:

This is not a complete list - in fact it is barely a list. Please add a comment to point out what I am missing.

- Code Academy - A free on-line coding tutorial that is interactive and problem based. They offer tutorials for JavaScript, HTML, PHP and help you learn how to build web projects. Very cool and free.

- GitHub Learn GeoJson - GitHub is a place where programmers, especially those working on the OSS space, keep their code for others to download, use and improve upon. This is made by Lyzi Diamond.

- Maptime! - An awesome list of mapping resources by Alan McConchie (@almccon) and Matthew McKenna (@mpmckenna8).

- Spatial Analysis On-line - As I try to remember my GIS courses, this is the on-line text that I reference to help me understand the analysis I want to run.

- Mapschool - Tom MacWright wrote this as a crash course in mapping for developers.

Colour and Maps

Because maps should be beautiful, I use these colour palette websites to make them easy to read and colourful:

Finally, NASA has a great 6 part series on colour theory called the "Subtleties of Color".

Naming is Colonialism

Take a look at a map of Edmonton. A close look, here or Google Maps would also do, here.

What do you notice? Roads? Maybe the map colours? Or perhaps the neighbourhoods? There's the river; and my house is around here (I always look for my house, or the house I grew up in).

Sure.

Look again at the names.

Windermere. Keswick. Ambleside. Empire Park. I could go on (and on).

In fact, of the 1300 or so named places in Edmonton, the vast majority of them represent the names of places, or people, from the United Kingdom or Western Europe. Of those 1300 or so names, less than 130 represent the First Nations or Metis peoples who currently here or who lived here prior to Edmonton being "discovered" in 1754 by Anthony Hendey. Less than 130; that is about 10% of Edmonton's named places represent FNM peoples, and most of those FNM names are not culturally or geographically significant.

[Place names]…play an important cultural role by identifying our societal values and by serving as a medium to commemorate people and events.

Government of Alberta Geographic Names Manuel (2012)

As Berg and Kearns (1996) state, “…naming places reinforces claims of national ownership, state power, and masculine control” and as such act as an explicit tool of repression. If you want to claim the narrative of a colonized place, name it after your places and people from where you came.

If we were to peer under this veneer of Britain, to peel back the thin layers of Monarchs and the Lake District, we would find a deep and yet largely unknown (to settlers) FNM history including a vast web of named places. What is it that prevents settlers from knowing this past? What does that fact say about the relationship between FNM peoples and Settlers?

Edmonton and its surrounds have been in use for at least 8000 years. Area archaeological sites date back to 6000 BC. To put that into perspective, if Settlers have been here for 2.6mm (remember that Edmonton was discovered in 1754), First Nations people have been occupying and using Edmonton for 8cm.

That is a thin veneer of Britain indeed.

Edmonton has been occupied for over 8000 years by First Nations people, and yet the vast majority of Edmonton place names are drawn from a thin veneer of settler occupation of the last 262 years.

Mental Maps

A mental map is an 'inner eye' representation of how we think of a place. Mental maps reflect the deep and nuanced understanding of place (those locations that are important to us) that each and every one of us posses, and Edmonton has millions of mental maps representing millions peoples thoughts on place.

The one pictured below is from my MA research. This image was captured from a 45 minute video of a person (an 'informant') drawing their mental map of Goldbar. The informant also discussed, in great detail, all of the features that were being drawn, and the memories each one invoked. The following quote is a short excerpt (from over 10 typed pages of description) of his memories of this place.

A mental map of Gold Bar (Dance, 2012).

There was a path in the woods there, and we call that Moonies run because our teacher, Mr. Moonie, lived right there. My friend played guitar and I played guitar, and we used to take our amps, carry our amps across back and forth across the river. At this point here right in the middle of the bridge was we deemed that as perfectly half way, so we would say, ‘Okay, I’ll meet you on the bridge’. But yeah, I spent a lot of time down there, in Gold Bar.

Place

A place is comprised of its physical characteristics, the activities that occur there, and the meanings derived through interactions between users, their activities, and those characteristics (Dance, 2012). Places define how we see and use an urban area. Places are those locations that offer vibrancy and connection within a city, and focus our desire to live in a specific location.

And a place name is nothing more than short hand for all those nuanced layers of meaning. Place names are important, and Edmonton does not adequately recognize those people who have called this place home for 8000 years. In fact, the continued lack of formal process that acknowledge FNM place names in Edmonton is colonialism. For a city in Reconciliation I would expect policy supporting the naming of Edmonton's places for historic FNM places names.

It's almost as though we Settlers are trying to deny a history.

Policy

The Naming Committee policy (specifically, Policy C509B) states that the purpose of the Naming Committee is to:

- Establish naming criteria;

- Establish principles for the naming of development areas, parks, municipal facilities, roads, and honorary roads, and, if requested by the City Manager, components of municipal facilities;

- Establish principles to recognize former Mayors; and

- Establish principles to recognize former Councillors.

Furthermore, The Naming Committee Bylaw 17138 [PDF] stipulates that 'The Naming Committee will establish and maintain The Names Reserve list.' and that City Council can appoint members.

While it is necessary to recognize former Mayors and City Councillors, it is even more important to recognize first peoples. That will not occur in a meaningful way until it is reflected in policy.

Reconciliation?

Current City of Edmonton place naming practice (supported by policy) is colonial in that settlers are imposing British names on an already named landscape:

- Current place names are overwhelmingly British in origin;

- Policy supports the naming of places after council members and the Mayer, yet doesn't explicitly support historic or cultural FN place names;

- The Naming Committee is empowered to establish a reserve name list, yet there is no policy direction for the Naming Committee to research FN place names that are historic and culturally relevant.

If Edmonton is serious about reconciliation should that not be reflected in policy? If we are serious about reconciliation, should we not demand that it be reflected in City policies?

If we were to address these process shortcomings, naming Edmonton could be an act of reconciliation.

Naming Edmonton Project Update

I cannot believe the uptake that this project received from Edmonton's open data community. I had several people step forward and offer to help including Catherine Szabo, Mack Male and Aaron Budnick. Despite this enthusiastic response, though, I am going to defer the start of this project until early March for one very good and exciting reason: The Edmonton Public Library has asked that we partner and make Naming Edmonton a community project. Great, right? But what does it mean?

While we have not discussed the details as of yet, I can say that Naming Edmonton will be featured on Open Data Day, and from this I can also imagine a much higher profile and thus greater citizen take up and engagement.

Citizen involvement is important to the project's success for a bunch of reasons:

- Technical support - we could sure use some help migrating a lot of word files to excel;

- Defining a work plan. I know it's boring, but having a plan to get from Ada to Zoie would be helpful in knowing what to do;

- Thoughts on what the name data could be used for, this will help define some additional columns that we could crowdsource, and;

- Naming Edmonton will need a huge number of people willing to populate the empty spreadsheet - in effect filling up the 10000 cells that will complete the dataset.

It's an ambitious project, and will require a large crowd from which to source data, but I think with the right plan and exposure we can do it.

What do you think? Let me know.

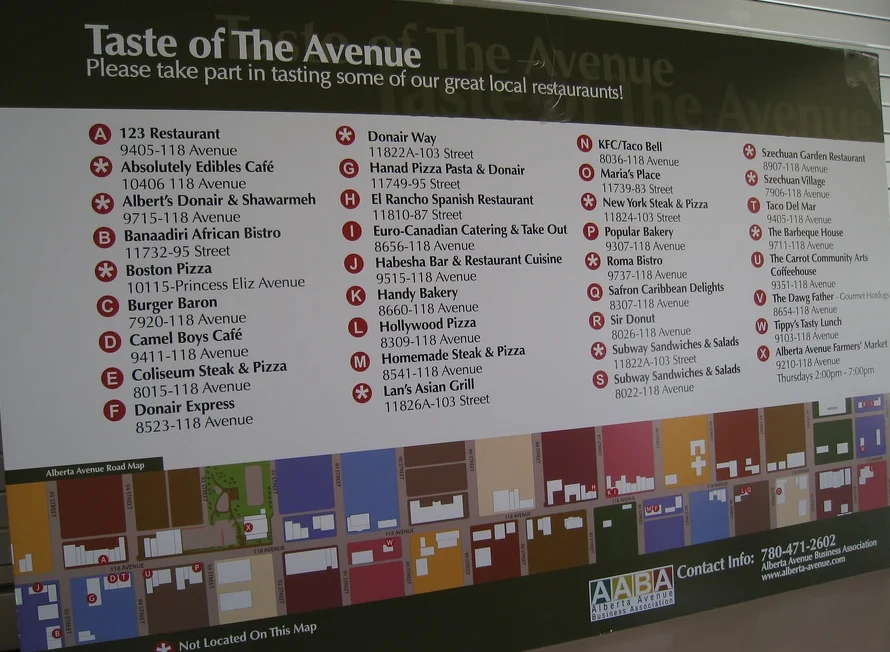

Alberta Avenue

The image above was taken by Mack Male and can be found on Flickr. The idea for this bloig post came from a comment that R90S made. I will follow-up with more comments in the coming weeks.

Introduction

This post will draw heavily from the City of Edmonton's Alberta Avenue Neighbourhood Housing Profile (2014). A PDF download of that document can be found here. Please note that all conclusions drawn from the data presented are mine, and not the City of Edmonton's.

The purpose of this report was to:

...allow stakeholders and the City of Edmonton to identify specific housing policies, programs and pilot projects with strong potential for improving neighbourhood housing conditions in five inner city neighbourhoods: Alberta Avenue, Central McDougall, Eastwood, McCauley and Queen Mary Park. (Page 4)

Furthermore, the report states that:

...the neighbourhood is transitioning from a typical “inner city” to again become a desirable place to live and raise children. Housing is more affordable here than in most of Edmonton and more families are moving here. Revitalization efforts, coming from the community, arts groups and the City, are making neighbourhoods such as Alberta Avenue more attractive to families. (Page 6)

Income

The data presented below can be found on on pages 19-20 of the report.

Alberta Avenue average household income grew by 64.4% from 2001 to 2011 and is $60825/year (2011). Edmonton's average household income in 2011 is $90340.

The household income ranges are as follows:

- 29.6% earned less than $30000 in 2011, down 50.5% from 2001.

- 27.3% earned between $30 & $60000 in 2011, down from 30.1% in 2001

- 43% earned more than $60000 in 2011, up from 19.4% in 2001

- According to Stats Canada after-tax low-income measure, 18.7% of Alberta Avenue residents are considered low-income.

Housing

Housing data for Alberta Avenue can be found on pages 24-27 of the report.

From 2001 to 2011, the average monthly rent has increased $353 to $887 per month. The average resale price for a house in Alberta Avenue increased $104 410 from 2005 to 2013. In 2013 the resale price is $225 188. The average duplex sells (in 2013) for almost $293 000, up 86.2% from $157167 in 2005. There are, as of 2010, 274 non-market affordable housing units, representing 6.1% of Alberta Avenues units.

Households earning minimum wage ($9.95/hr or $20,696/year), or collecting social assistance such as Alberta Works ($323/month core shelter payment for private housing) would not be able to afford the average rent or resale house price for this neighbourhood. (Page 29).

Summary and Conclusions

In the period from 2001 to 2011, the number of households earning over $60K in the neighbourhood of Alberta Avenue increased by about 24%, while at the same time, those earning less then $30K decreased by 50%.

Also from 2001 to 2011, rent has increased 60% and the resale price for the average house has gone up 86.4% and for a duplex, 86.2%.

By these metrics it seems that lower income people are being displaced by wealthier Edmontonians in (on?) the Alberta Avenue neighbourhood. This is in line with the conclusions of the report, and with the language used to describe the changes occurring in Alberta AvenueI. Further more, specific language such as "...transitioning from a typical “inner city” to again become a desirable place to live and raise children (page 4)" imply that gentrification is not only occurring, but that is is a desirable outcome.

While gentrification may be inevitable, there are both positive and negative outcomes.

The tension between the positives and negatives of gentrification will be explored further.

PLEASE NOTE: I am looking for specific policy options that Canadian cities have in place that curb or support gentrification. Please drop me a note or leave a comment with a link if you have any insight into this. Thank you!

Naming Edmonton: From A to Z

Dear Edmonton (and the World),

I need your help; I would love some project collaborators with technical skills.

A number of years ago I happened upon a copy of Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie by the City of Edmonton and published by the University of Alberta press. I was intrigued by this old type of document, a gazetteer that provides lengthy descriptions of Edmonton's places, including the origins of the name and their geographic location within Edmonton.

But the book also provided insight into Edmonton's lost names. Who remembers the Rat Hole, the tunnel under the CP rail line on 109 Street at about 104th Avenue? Or Namao Avenue, now 97 Street?

This book provided a glimpse into our past, and documents how Edmonton's names came to be - those in use now, and those no longer in use and at risk of being lost. As a physical document, it is in many ways as dated as the notion of a gazetteer, something to be held and admired as if it's an antique from the 18th Century.

Except that it's not an antique, or even physical as I have an electronic copy of the book, and permission from the publisher to transform this collection of Word docs into an open data set similar to the Aboriginal Edmonton dataset. Aboriginal Edmonton was a small scale collaboration between me, the City of Edmonton and Edmonton Archives. We were able to take this small dataset (about 187 lines in Excel) and transform it from a collection of Word documents into a table that included coordinates, name origins and name description. These data, pictured in part above, can be found in the City of Edmonton's open data catalogue.

I think it would be valuable to transform the Naming Edmonton dataset in the same way - but, I need your help. For this project to work, the Word files that contain about 10 000 names have to be transformed into structured Excel files that will allow a group of people to add pertinent data, such as coordinates, and to verify existing data. So, the first step is to, somehow, computationally transform and structure the data.

If you have any ideas, and want to help, please get in touch either through this blog, on Twitter of via email.

Thanks,

Matt

Riverdale

Header photo by Randall (taken in 1991) from Flickr.

Introduction

The intent of this case study of Riverdale is twofold - to investigate how likely it is that Riverdale is being gentrified through an examination of a variety of data including income, ownership & rental rates, length of residence and building permits; and to test out my method of examination given the data that I have on hand.

Riverdale is a wealthy community with 44% of households earning over $100 000. A further 21% of households earn over $80 000, and 25% of households earn less than $50 000 per year. These data are form 2010 and are found in Riverdale's Demographic Profile produced by the City of Edmonton. All other data reported in the post are from the City of Edmonton's open data catalogue.

Ownership and Rental Rates

From 2009 - 2014 the total number of housing units increased from 940 to 965. The number of single detached houses increased by 14, row houses by 51, and apartment units by 18. Duplex/triplex/fourplex decreased by 58. These numbers seem to indicate that the land occupied 'plex' units were used to build single family homes and row/apartments.

While I have rental and owner data for 2009, 2012 and 2014, the rate of 'no response' for the 2014 data ranges from 23 - 28% for single-detached, 'plex',and apartments. Row houses stand at a 'no response' rate of 5%. I will, therefore, not consider the 2014 data.

Between 2009 - 2012 ownership rates in Riverdale have decreased for most housing types (please see Figure 1), but most precipitously for row houses which saw an ownership decrease of just under 80% (from 84% in 2009 to 15% in 2012); apartments (1-4 stories and over 5) decreased by 9%. Ownership of single detached houses increased by just over 5%, and 'plex' ownership increased by 24%.

Rental rates for the same time period, 2009 - 2012 (Figure 2), decreased for single family homes (7%) and 'plex' buildings (24%). Rental rates increased for row houses by almost 70%, and by 7% for apartments (1-4 stores, and 5+).

Building Permits

The building permit data spans from 2009-2015 (see Figure 4: Summary Table of Riverdale Building Permit Data). The vast majority of build permits were issued for building new single family houses - 37 were demolished to 45 builds indicating that there were 8 new houses built on land not perviously occupied by a structure. The 45 builds represents 4.5% of the 965 residences in Riverdale, and cost almost $15 million to construct. Detached garages were big, with 47 detached garages being constructed valued at $342 000; most of these garages were built in conjunction with a new house. 11 new semi-detached houses were built costing a total of $4.7 million.

In contrast, the new 'lower value' dwellings - apartments, duplex's and row houses - were not constructed at all, and only showed a very modest number of interior or exterior alterations (see Figure 4).

Demographics

From 2009 to 2014 the demographics of Riverdale have shifted. Specifically, there was increase in the number of men and women in the 60 to 80 year old cohorts (135 people), the 35 - 39 (19 people) year old cohort and 0 - 4 year old cohort (9 children). All other cohorts saw a decline for a total of 259 people. The 2009 census had a no response rate of just under 10%, while the 2014 census had a no response rate of close to 15%.

Conclusions

In summary, ownership rates are down for all housing types except single family homes and 'plex' homes. Similarly, rental rates are up for all housing types, except 'plex' and single family homes. The most striking change is in row housing which saw a decrease in ownership by 80% and an increase in rental rates by 70%.

In addition, the vast majority of renovations, including new builds, were allocated to single family homes - 45 new single family homes, as compared to 0 new homes for all other housing types.

Finally, Riverdale is seeing a decline in all age groups except for 0-4. 35-39, and 60-80.

I think that there are a number of gaps in this data. Specifically, I would have liked to have seen time series of income data to see home family income has shifted and time series housing sales data, and school enrollment data for the Riverdale PS. I would also have liked to see a higher response rate for the 2014 census data. That said, I think I can draw some broad conclusions.

1. Middle aged people are being replaced by senior citizens, and those at the upper end of the child bearing years, and perhaps their young children.

2. The housing market is shifting from owning to renting, except for single family homes and duplex/fourplex, where ownership rates are up.

3. 4.5% of older single family houses are being replaced by new builds.

I think that Riverdale, while not being gentrified in a classical sense of having a primarily low income population be replaced by a higher income population, is seeing a shift based on money. I suggest that those who can afford to are buying the older and smaller houses, where a small portion (4.5%) of those single family homes are being rebuilt. I think the larger trend is for older people (the 60-80 demographic) to retire in Riverdale with it's close proximity to downtown and nestled within the river valley - close to trails and quiet. The smaller trend is for high income families to settle here with their young children.

Those who are younger, with no family or with an income of under 50K are renting the older apartments and row houses. I have no idea why the row house ownership plummeted.

What are your thoughts? What did I miss, or are you seeing an alternative story with these data? Please let me know.

Bookending Gentrification

This will be my last blog post for the next couple of weeks while my kids are out of school for the winter break. I'll be back on 06 January 2016.

The term 'gentrification' is limited.

It is limited in that it only describes the outcome of a power imbalance that exists between those who are displaced but who already rent or own, and those who are doing the displacing.

As Smith (1982) states:

"By gentrification I mean the process by which working class residential neighborhoods are rehabilitated by middle class homebuyers, landlords and professional developers. I make the theoretical distinction between gentrification and redevelopment. Redevelopment involves not rehabilitation of old structures but the construction of new buildings on previously developed land. (Gentrification (2008)"

As a term, gentrification is limited in the process it describes, the people who are affected and the outcomes achieved. I have called this 'Classical Gentrification' after Elise Stolte's use of the term in a comment on a previous blog post.

This classical gentrification has a number of process based theories (demographic, social, political, and economic) associated with it (please have a look at the Gentrification Wikipedia page for an overview). These are important theories that warrant a close look and contextualization to Edmonton.

But, none-the-less, the term gentrification is limited - as it should be. If the term was too broad we would not be speaking about anything specific.

Spatially, gentrification references neighbourhoods, and not spaces that are smaller - such as blocks or specific development projects - or bigger, such as entire cities. Or spaces that straddle neighbourhoods, for instance a community that may cross a neighbourhood line.

Temporally, gentrification pre-supposes that developments (houses, apartments, etc) are already built and occupied, and as such ignores those spaces that are undeveloped. Even the term 'development' is problematic. Who is determining that an area is not developed, or is under-developed?

Gentrification is focussed on physical places and mostly ignores a range of non-physical attributes that may be associated with a place. Sure, more recent conversation of gentrification does include the dissolution of social structures that occur when people are displaced (please have a look at the article about Regent Park in Toronto). But gentrification does not address the non-physical attachment to a place that can be reflected in place names or historical uses / buildings.