Neogeography of Edmonton's River Valley

Neogeography of Edmonton's River Valley

from

Abstract

Presented at Carto2013 on June 14, 2013.

Place can be defined as the meanings that are created at the confluence of location and activity (Relph, 1976). The places that comprise an urban environment are increasingly networked through the ubiquitous disbursement of connected, hand-held, location-aware mobile devices (Castells, 2004). This, coupled with the evolution of the GeoWeb supporting volunteered geographic information (VGI), is defining a key method of citizen engagement with spatial data and information. Specifically, citizens are able to communicate place-based information through these technologies. These emerging phenomena give rise to some pertinent questions: (1) To what extent are GPS systems able to capture users' understanding of location, and; (2) How do people contribute spatial information to the GeoWeb?

Using a case study method that centered on Edmonton’s river valley trail network, 17 informants were interviewed regarding their use of GPS devices in the capture and communication of spatial information, and their corresponding knowledge of place. Our findings indicate that people possess and are able to articulate place knowledge that is deep and personally meaningful, especially in regards to parts of the river valley they use and enjoy most often. However, location-aware mobile devices do not currently provide the tools necessary to communicate users' deep understanding. We conclude that current web based maps that support VGI only allow for a small portion of knowledge to be uploaded. This knowledge is restricted to the structure or form of a place, rather than its meanings or context.

Alberta's New Open Data Portal

A few weeks ago I was asked by the GOA to look at their new Open Data Portal and make some maps with the data. I did, and the maps can be found at my MapBox site. While I think that these are beautiful and interesting maps that tell a story, the important narrative is one of open. Open, in this context, implies a workflow that uses open source software to take freely available data and extract meaning from that data. In this instance, I used QGIS and TileMill, coupled with PostGIS and Open Street Map couple with Natural Earth as the base map layer. These maps are hosted by MapBox. All if it, for free or mostly free. I pay a small subscription to host my maps, but MapBox does have a free option. And these are not the only tools - Google Maps and ESRI also have a range or mapping tools for free.

This context of open includes the users; who are the open data users within this emerging ecosystem open tools?

(1) Government. Either those in the same government from other departments who just need some data to do their job, or other governments all together. When we developed emitter.ca, I was told by an Environment Canada friend that it made there life easier because the data was more readily available and visible.

(2) Journalists. For instance @leslieyoung wrote about her difficulty accessing oil spill data from Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development here. If these data were available in an open portal, journalists could more easily access it for their stories. We want this as the open data provides transparency and accountability.

(3) Researchers and developers can use the open data as the 'base map' or core data sets upon which they place other data or code to extract greater utility. For instance, heath indicators are a great open data set that can take on greater meaning when coupled with research based data such as smoking rates or ambient pollution. Perhaps a developer would build an app that could indicate where NOT to go based on these same health indicators (not that I am advocating this...).

In short, the Open Data Portal is meaningful only when it provides data that can make the data provider uncomfortable and accountable. Financial records (GOA's are here), environmental performance (including, yes, oil spills), meaningful health indicators such as cancer rates or respiratory illness by a reasonable (and privacy protecting) geographic region. These are the squirm inducing data sets.

In this instance, with it's newly launched open data portal, the Government of Alberta has made a bold first step in committing to path of openness and transparency. But, by in large, the data presented in this first iteration are not challenging or likely to make the GOA squirm. Farmers market locations and schedules, eco zones, sensitive species. Nice and interesting, but not hard. The hard data will relate to the oil sands and oil transportation network within Alberta. These data will document health outcomes by health region; will undercut the substantive pay wall that the ERCB has around the most valuable data (see here). So, a great first step, but only a first step. The hard work is yet to come.

In the mean time, have a look at the portal, and please peruse the pretty maps I made, and let me know what you think.

Edmonton Population Density

Below is my first interactive map, published on the web! I used Map Box and Tile Mill technology to move from a CSV and Shape files to this map. The data came from data.edmonton.ca. Please explore and let me know what you think!

[mapbox layers='mattdance.Edmonton_Population_Density' api='' options='' lat='53.54079999999999' lon='-113.51039999999999' z='11' width='800' height='800']

What we DON'T know about smog in Edmonton.

As reported in the Edmonton Journal on 13 February 2013, Edmonton was under a week long air quality advisory due to elevated levels of particulate matter (PM), a constituant of smog. The smog was detected at two of the three AESRD stations in Edmonton - Edmonton East and Edmonton Central. From Alberta Health Services, here:

Precautionary air quality advisory lifted for city of Edmonton

February 13, 2013

EDMONTON– Alberta Health Services has lifted the precautionary air quality advisory issued February 6, 2013 for the city of Edmonton.

Monitoring indicates air quality in the city of Edmonton is no longer being impacted by the temporary air-inversion event.....

Information about the air quality in some areas of the Edmonton Zone is updated regularly on the Alberta Environment Air Quality Website:http://environment.alberta.ca/0977.html. Air quality information is also available by phone, toll-free, at 1-877-247-7333.

The reporting of this air quality event was thin in many respects. What causes smog in general, and what caused the smog in this specific event? How do we know the extent of the problem, and is there any way to identify the pollution sources that are contributing to the problem? I will attempt to answer these questions.

The USEPA defines smog as...

...a condition that develops when primary pollutants (oxides of nitrogen and volatile organic compounds created from fossil fuel combustion) interact under the influence of sunlight to produce a mixture of hundreds of different and hazardous chemicals known as secondary pollutants. Smog is the brownish haze that pollutes our air, particularly over cities in the summertime.

As indicated by the USEPA, smog is more commonly found in the summertime. In Edmonton, for the week of 06 - 13 February, a health advisory was called as a result of vehicle and other emissions being trapped under a temperature inversion, where the temperatures aloft are warmer than those on the ground. In this instance, the temperature inversion acted as a cap, not allowing the pollution to dissipate by wind. The Edmonton Journal article also indicated that the smog was a result of vehicle emissions. How widespread is the 'problem' of vehicle emissions, and how to we track them?

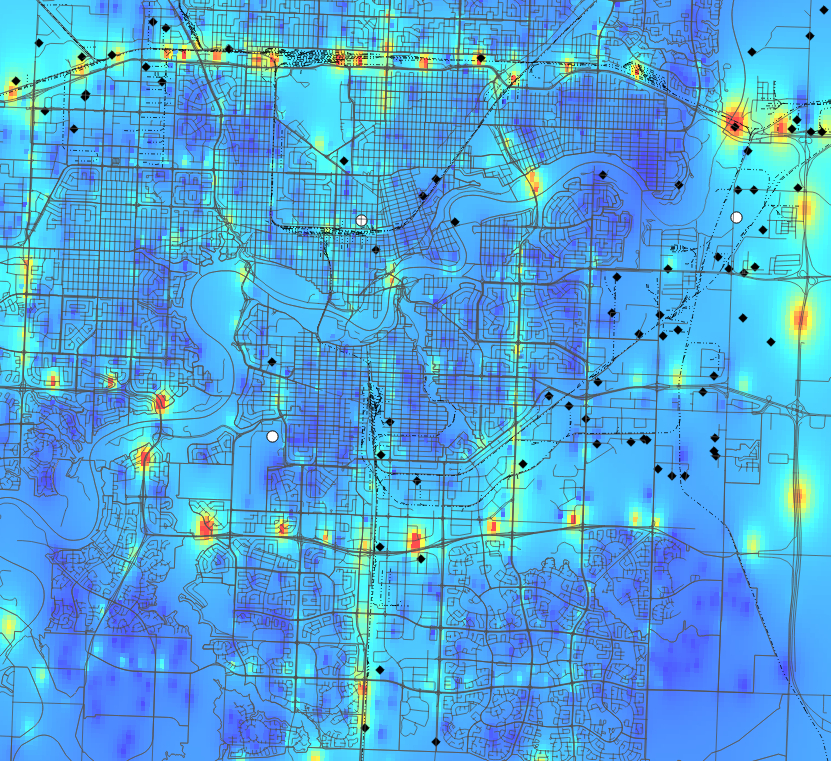

The following map of Edmonton does NOT depict air pollution. Rather, it indicates where some of the sources of air pollution are, and where the monitoring takes place that tracks these pollutants.

The Map: The black diamonds indicate industrial emissions sources from the NPRI database found within Edmonton. The white circles are the Alberta Environment run air monitoring stations, and the colour layer indicates density of traffic from the City of Edmonton open data catalogue where I ran an IDW analysis to define a 'topography' of traffic flow - the blue is no or low traffic density, yellow moderate and red high (the highest volumes of traffic are over 100 000 vehicles per day, and the lowest less than 50). Rail lines are dashed. I do not indicate other emissions sources such as light or moderate industrial activity that would not report under the NPRI.

It is apparent from the map that there are many 'hotspots' of high vehicle flow, most notably on the Yellowhead, Whitemud and Henday. There are also some smaller pockets of high traffic flow in the downtown core, along 57th Street / Wayne Gretzky Drive, and Gateway BLVD. Environment's monitoring is located in the downtown, east Edmonton, and SW Edmonton. It is worth noting that the downtown monitoring station is on the top of a small building.

These regional monitors are great at pickup large are trends over time and are vital to the AQHI network, which is national in scope. There are three main issues with this AQ network: (1) it is limited in geographic area; (2) it is not at street level, and; (3) it is expensive to install and maintain.

So, we don't know the relative contributions of vehicle emissions vs other sources such as industrial or rail. We don't monitor or even really model in a public way vehicle emissions (The Clean Air Strategic Alliance, in 2007, released a ROVER report documenting vehicle emissions on Alberta roadways - the CASA link to the ROVER 2 report is broken, but I have a copy if you're interested), and so we cannot even speculate on the extent of smog pollution in Edmonton. This is a problem as the City of Edmonton becomes more urban, denser and bigger. How many cars can we add to the roadways, and how do we balance this with an appropriate amount of 'alternative' transportation options?

Why I don't support mandatory helment laws.

Please skip to 4.0 Conclusion for the abridged version of this long post. 1.0 Introduction I wear a helmet when I bike, and cannot imagine cycling without one when either road riding, mountain biking or on a family ride. I am uncomfortable without a helmet and feel vulnerable to injury by cars and my own stupidity - I have fallen off my bike often enough to know that for me a helmet is probably a good idea. Furthermore, I am trying to instill this habit with my children; they always have a helmet on when they get onto any self propelled wheeled vehicle. To my mind, there is no downside to wearing a helmet as long as you cycle within your ability.

But, having said the above, I am not certain that mandatory helmet laws are effective in preventing head injuries. In fact, I wonder if the bicycle helmet debate distracts us from a harder discussion on road safety and risk. I think that it is easy to have a public debate about a fringe group of cyclists and how they should be safer, rather than focus on road safety which would include slower residential speed limits, impact road and urban design, and be more difficult to reach consensus. After all bike helmets save lives, right? I am not sure, and so I am looking to answer the following questions:

A. Do mandatory helmet laws prevent head injuries?

B. What are the consequences, intended or otherwise, of mandatory helmet laws?

C. Are there better ways to protect cyclists?

I am writing within context of Alberta, which has had a helmet law since May 2002 that applies to children under the age of 18. Furthermore, this is a first attempt at understanding a complex issue. Please help me understand you position, comment below!

Please note: I AM NOT ADVOCATING A BEHAVIOUR. I WEAR A HELMET, AND SO DO MY KIDS. YOU CHOOSE WHAT IS BEST FOR YOU!

2.0 Evidence Based Policy I don’t think that it is correct to assume that helmets save lives, just as I don’t believe that climate change is a hoax because it is −20C in Edmonton while I write this. Where there is a hypotheses related to policy, there should be a way of collecting data to test that hypotheses. In other words, good public policy is not made from individual cases, anecdote, or from a gut feeling, but rather should be made from a position of informed choice where all viable options and outcomes are examined through the lens of data analysis. The final policy choices may be made for political reasons, but at least these are informed decisions. Medicine is an example where evidence plays a big role in determining best practices. As discussed here, evidence based medicine (EBM) is the “…conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions…”.

Every time (I hope, but perhaps this is a pipe dream) you go to an emergency department, see a medical specialist, or have a procedure done, you rely on this process to get the best results and safest treatment (otherwise you see a naturopath). Evidence based decision processes do not have to be limited to medicine, we can expect the same rigor for public policy, in general, and within the helmet debate specifically. To that end, I plan on examining the evidence that addresses my questions.

3.0 What does the data say? Three types of data should be considered when assessing whether cyclists, by law, should be required to wear helmets - (1) bicycle / vehicle collisions and (1a) bicycle incidents that are comprised of falls or collisions with stationary objects or other bikes, and (3) emergency room visits related to bicycling accidents. These data should be looked at within an Albertan and international perspective. To give a relative risk, pedestrian data will also be examined. Caveat: I don’t have total numbers of cyclists and pedestrians - so their is some interpretation going on here based on totals numbers.

3.1 Bike, pedestrian and vehicle interaction in Alberta The following data are taken from Alberta Traffic Collision Statistics 2010 (found here [PDF]) , and represent the number of incidents for 2010.

| Road User | Killed (N) | Killed (%) | Injured (N) | Injured (%) | Total (N) | Total (%) |

| Drivers | 185 | 53.8 | 11012 | 60.3 | 11197 | 60.2 |

| Passangers | 65 | 18.9 | 4528 | 24.8 | 4593 | 24.7 |

| Pedestrians | 35 | 10.2 | 1129 | 6.2 | 1164 | 6.3 |

| Motorcyclists | 31 | 9.0 | 683 | 3.7 | 714 | 3.8 |

| Bicyclists | 6 | 1.7 | 467 | 2.5 | 467 | 2.5 |

| Other | 22 | 6.4 | 450 | 2.4 | 462 | 2.5 |

| Total | 344 | 100 | 18253 | 100 | 18597 | 100 |

These data were copied from Table 3.1 of the Alberta Traffic Collision Statistics, 2010

3.1.1 Observations I am surprised that more pedestrians were killed and injured than bicyclists in 2010. 1164 pedestrians (6.3% of the total) as compared to 467 bicyclists (or 2.5% of the total). These are interesting numbers, but not really relevant unless we know the total number of pedestrians in Alberta vs. bicyclists. Or even better, the total number of kilometers walked by pedestrians vs. the total number of kilometers cycled by bicyclist. In this latter case, we could then calculate injuries and deaths per kilometer travelled for each case. It would also be interesting to factor motorcycles into this mix. A side note. The raw numbers clearly indicate that about 2.5 times more pedestrians were killed than cyclists in 2010 and yet no one is suggesting that pedestrians wear helmets.

3.1.2 Other observations from the Traffic Collision 2010 report From the same report, Table 9.4 indicates that “Casualty rates per 10 000 population were highest for persons between the ages of 15 and 19”. The lowest rates were for those under 5 and over 55. 27.1% of bike accidents due to the cyclist disobeying a traffic signal, and 13.5% due to the cyclist failing to yield the right of way at an uncontrolled intersection.

From Table 9.3, 9.2 and 9.1 - most accidents occurred on weekdays between 3 − 7PM (rush hour), in June. From Section 8 of the report; Pedestrians faced the similar hazards, with most vehicle, pedestrian interactions occurring during rush hour, in October. It is interesting to note the language of the report points to the actions of the drivers being responsible for pedestrian injury (rather than pedestrians being responsible for their own injury) or death, versus the action of the bicyclist being responsible for their own injury or death.

3.2 Cycling rates and ER admittance The section will draw upon a PhD thesis, from the University of Alberta, written by Mohammad Karhaneh in 2011. Commentary and insight on this thesis was found here. . Karhaneh notes the following based on pre- and post-law observational studies completed in 2006:

- There was a large decrease, 56%, in children’s cycling from 2000 to 2006.

- There was also a decrease in teenage (13-17YO) cycling at 27%

- A 21% increase in cycling for adults.

In his dissertation, Karhaneh simply notes a decease in the number of people seen in the ER as a result of cycling injury. He does not create a ratio of cycling injury to the number or rate of cycling in the population (from cyclehelmets.org). In contrast to the decline in cycling, the rate of injury seems to have gone up after a mandatory helmet law was legislated. As cyclinghelmets.org notes:

“The number of children treated in emergency rooms for non-head injuries was an average of 1,762 per year in 2003-6 compared with 1,676 in 1999-2002, despite there having been a fall of 56% in children cycling over the period. For teenagers the average number of injuries rose from 870 to 1,101 per year while the amount of cycling went down by 27%.”

4.0 Conclusion

This is a complex issue that involves many factors, and I have only offered a slice of the available data, with some commentary that makes sense to me provided by cyclehelmets.org. I have not touched on most of the available data, nor have I explored the physical limits of helmets as protective equipment (see here [PDF] for an overview). I have also neglected to look at injury rates in other jurisdictions that have slower residential speed limits, dedicated cycling lanes and a stronger bike culture. I could complete a PhD on this question, and in fact some have - perhaps this complexity and depth of information is a barrier.

To summarize, it seems that helmets are of use for a limited population in certain circumstances, as in children cycling at slower speeds who fall a shorter distance onto smooth ground. As soon as the speeds increase, and the falls become more complex (uneven ground, impacts with other moving objects such as cars, etc.), the protective benefits of a helmet are negated. Male children 15 - 19 seem to be the most at risk of injury - the data indicates that they are, as a population, more reckless, and take greater risks beyond the capacity of a helmet to manage. In fact, it is speculated, that if they were not wearing a helmet, that 15-19 YO males might not take so many risks. In other words, the helmet was perceived to offer more protection than it does. This finding can be extrapolated more widely to account for the general increase in head injury found in Alberta AFTER the introduction of bike helmet laws. People take more risks when they think they are protected + the limited protection afforded by a helment = more cycling injuries.

I also got the sense from the data that a culture of cycling was protective against injury for those who commute. Dedicated bike lanes, more bikes on the road and drivers who were more aware seems to make roadways safer. I also wonder about residential speed limits for overall road safety. What if we were limited to 30KM/HR rather than 50?

Finally, the data also seems to indicate that the perception of cycling as a dangerous activity dissuades people from riding, leading to two unfortunate outcomes: (1) those who do not cycle, don't gain the health benefits, and this could be significant given increases in obesity, and; (2) spontaneous Bixi Bike type trips are less likely to happen in those jurisdictions that have helmet laws.

“In general the rate of head injuries is declining, but this is not consistent across the country, nor is it attributable to legislation as some provinces with legislation experienced a decline while others did not.” Middaugh-Bonney T, Pike I, Brussoni M, Piedt S, Macpherson A, 2010. Bicycle-related head injury rate in Canada over the past 10 years. Injury Prevention 2010;16:A228.

AQ Egg: First impressions

My Kickstarter contribution has finally paid off! My Air Quality Egg has arrived in the mail! To recap, the AQ Egg over-reached its funding goal in April 2012. The project had asked for $39 000.00, and raised over $144 000.00 with 927 backers. Impressive. And scary. As we soon learned, their were high expectation, and the egg almost hatched as vapour-ware (an impressive timeline can be found here). In short, what was promised in July 2012, was shipped in January 2013. What shipped, sadly, is not what I had expected.

Given the extra time that was used to create the egg, I was disappointed at how 'cheap' and flimsy it felt. In removing it from the shipping box, the sensor pictured at the base of the left egg became loose and fell out. The egg, which is 'snapped' together via a vertical seam that runs around the device, was not properly 'snapped'. It was loose and I was able to easily pull the shell apart. Furthermore, when reading the directions on how to set the sensor up, I was surprised to learn that they shipped some of the eggs, and unknown numer of them, with a software bug (the details here).

My Kickstarter contribution has finally paid off! My Air Quality Egg has arrived in the mail! To recap, the AQ Egg over-reached its funding goal in April 2012. The project had asked for $39 000.00, and raised over $144 000.00 with 927 backers. Impressive. And scary. As we soon learned, their were high expectation, and the egg almost hatched as vapour-ware (an impressive timeline can be found here). In short, what was promised in July 2012, was shipped in January 2013. What shipped, sadly, is not what I had expected.

Given the extra time that was used to create the egg, I was disappointed at how 'cheap' and flimsy it felt. In removing it from the shipping box, the sensor pictured at the base of the left egg became loose and fell out. The egg, which is 'snapped' together via a vertical seam that runs around the device, was not properly 'snapped'. It was loose and I was able to easily pull the shell apart. Furthermore, when reading the directions on how to set the sensor up, I was surprised to learn that they shipped some of the eggs, and unknown numer of them, with a software bug (the details here).

Needless to say, these are annoying details.

But, I am still a fan. While the NO2 sensor is not sensitive enough to pick up all but the highest spikes in NO2 (that we know as no one has consistently monitored busy roadways in Edmonton), it feels cheap, and it arrived months late, it still represents a remarkable revolution. No other AQ sensor offers such easy and inexpensive citizen access to AQ monitoring. Granted, you have to be rich and technically literate to deploy one of these things, but it is a step away from government controlled monitoring. It is possible to build or purchase at a low cost, and it is complete open sourced. In other words, you can download a component list, 3D printing schematics, and the code to build and launch your own sensor. I have to remember that I received a V.1, and as with many V.1, there are issues. But these issues will get ironed out in successive iterations as more people look at, and improve upon, the egg.

You can learn more about the Air Quality Egg here , and you can view my (empty for now) data stream here. I'll update this when I have my egg feeding data to the web.

Job Posting - Contract coder

Under Development

I am sorry about the mess presented here, but I am concurrently updating my site and learning Wordpress! Please have a look and let me know what you think!

Urban GeoWeb 1

This is an inaugural post, the first of a series that will explore the intersection of the Urban with the GeoWeb and Social Computing. My interest is specific to data visualisation, collaboration and access to resources that will enrich citizens experience living and working in urban environments. The GeoWeb is emerging (has emerged?) as a dominant platform by which people consume, generate and communicate spatially relevant information that is a reflection of their use and experience interacting with urban areas. Social Computing is that cloud of information and people / groups that surrounds us all, and that we access via a mobile devise or computer.

Transit is an obvious way to incorporate several data streams - open transit data which describes the bus schedule and bus stop locations, potentially GPS from individual buses - all displayed on an interactive map interface that supports queries. This is standard. Mapnificent is not standard as it displays all of the Google enabled transit maps in the world, and provide the user travel times. TripTropNYC creates a travel time heat map from any location of New York. Boston's Street Bump app utilises a smart phone's GPS and accelerometer to provide a realtime view of the state of Boston's roads. I love this this type of application development is seeking to crowdsource, through citizen based sensors, less expensive ways to track urban infrastructure.

Sustainable Cities Collective expands on this theme by discussing WikiCity as a way to engage citizens in city improvement:

Local groups all around the world are taking the initiative and are building the infrastructure that governments refuse or are slow to do.

Charlie Williams, an UK based artist, has created some very cool looking Air Boxes which provide realtime feedback to citizens on the quality of their air. These boxes sit at street level and simply shows a red, orange, or green graphic depending on the quality of the air.

Finally, the MIT Sensable City Lab hosted a Future Cities forum that brought together a number of leading thinkers, including Carlo Ratti the Lab's director, to discuss future cities. The video of these talks can be found here.

I'll close with these words from the Future Cites website:

Over the next few decades, the world is preparing to build more urban fabric than has been built by humanity ever before. At the same time, new technologies are disrupting the traditional principles of city making and urban living. This new condition necessitates the creation of innovative partnerships between government, academia, and industry to meet tomorrow's challenges including higher sustainability, better use of resources and infrastructure, and improved equity and quality of life.

Alberta's Expert Monitoring Panel

Last week I responded to an open call by Alberta's Expert Monitoring Panel to present my take on the following questions:

1. What should a world class environmental monitoring system look like? 2. What type of organization should manage and operate the proposed environmental monitoring evaluation and reporting system? 3. What kind of information should the environmental monitoring system produce? 4. How should the environmental monitoring system be funded? 5. Do you have any further suggestions or advice to help the Panel as they develop recommendations for a world-class environmental monitoring system?

As I didn't feel that I could adequately address each question, my presentation and argument focuses on components of Q1 and Q2. This blog post will focus on the Open Data aspects of Q2. My full presentation can be found here: Presentation to Alberta Environment Expert Panel on AAQM.

Slide #5 outlines the 3 Laws of Open Data as proposed by David Eaves, Slide #6 outlines the process of turing open data into a community good. Open Data is important in this context as it has the potential to engage a broader base of citizens in a conversation that is normally limited and closed. While engagement is possible it does not happen quickly or easily. If there was a formal process for turning open data into community engagement, it might like this:

Step One: Create An Open Data Catalogue

This open data catalogue should be indexed such that it can be found and formatted such that the data is readable by a computer. The data should also be supported by a generous licensing agreement that demonstrates trust in the community. Keep in mind that the data should be good and complete, but not perfect. If there are issues, the community that you build will find them and tell you.

Step Two: Engage a Community of Developers

There are a number of things that need to happen here: (1) create and Application Programming Interface (API) as an invitation for developers to access and use the data; (2) advertise that the data exists, and where it is; (3) link the core data with other support data, for instance a description of what the substances are, any location information and other meta data; (4) finally create an event or competition as a means of engaging developers. Something like and Apps for Air contest, coupled with a hack-a-thon.

Step Three: Get the Apps Out There

There are groups of smart phone and web users who love new toys. Ensure that these folks know that some cool Air Quality Applications are being developed, and invite these early adopters (and researchers) to use the apps and to provide feedback on them. Perhaps they can even vote on the winning application. In this instance, it is important to engage the early adopters through the smart use of social media tools such as Facebook and Twitter. Create a FB page, start using a Twitter hashtag, ask key members of the community for advise and help in getting the word out. Engage and don't be afriad.

Step Four: Wider Acceptance

As the apps start making their way onto the web and possible mobile devises, more people will use them and, hopefully, two things will happen over time. Citizens will realize that they have access to cool and useful tools, and the government will slowly become more comfortable with greater openness and transparency.

Conclusion

I was asked by the expert panel about brand protection. I believe that the best strategy to protect one's own brand is to engage with a community of people who support your goals and activities. That engagement is the best brand protection available. It is unfortunate that, to date, the Government of Alberta is too busy yelling things that we don't believe. More listening, engagement, and trust is required.

A more intelligent Edmonton?

Edmonton is on the cusp of great change. We are moving forward with an expanded LRT line, contemplating (seriously contemplating) building a downtown stadium for the Edmonton Oilers, and building a whole new community on the Municipal Airport Lands. For good or bad (likely good AND bad) we are moving forward and perhaps coming into our own as a major prairie urban center. I feel, though, that this change is in some regards being made with little understanding of the broader context, and that this context isn’t even on the radar in a meaningful way. Let me explain what I mean by this. For me, the best way to understanding something is to try and collect data and explore what those data are saying. And I think that this change is going to generate a lot of data – if we have the foresight and will to collect it over the longer term. Given my predilections towards humanities research and interest in air quality, I propose that we create a three-pronged network of monitors to help us understand the impact of change on Edmonton’s people, build environment, and air quality.

Edmonton’s People Edmonton is home to a great and increasing diversity of people who are impacted by ‘development’ in vastly different ways. For instance, business owners within the downtown core may have a different understanding of the potential benefits associated with a downtown arena than the working poor or other who use the Boyle Street services. The same is true for someone who lives in Riverbend, or downtown. The media is limited in the number of stories that can be printed, and the number of views that can be expressed. But there is another way to include more voices in the debate and as a record of impressions of change. What would it look like to document, through short-recorded interviews, the impressions that this diversity of people has regarding the change that we are seeing? These recordings could be grouped on a web-based map based on the location of the project being discussed. Over time a comprehensive public record could be created.

Edmonton’s Build Environment We are planning some large and impressive projects over the coming years and it would be a shame not to document, in detail, how these projects unfold. Interviewing Edmonton’s People is one approach to documenting these changes, and photographing the changes to the build environment is another approach. But rather than capture these changes with static one-off photos, we could with some thought, engage in a long-term photography project to run in conjunction with the interview project. There are several components to consider: Cowdsource: We can create a Flickr group and encourage citizens to upload their photos here with a geo- and other tags to help sort and understand the context. Time-lapse: Set up a number of self sustaining time-lapse rigs focused on key areas of development (the arena, the municipal airport lands, LRT routes) and let these cameras do their work. A picture a day (or two, or three…) over the course of a year will be a great resource into the future.

Edmonton’s Air Quality Establish a network of volunteers to travel through the city with mobile air quality sensors (there are options with this technology – MIT’s Copenhagen Wheel, or http://sensaris.com/product.html). Current monitoring practice has three sensors in Edmonton, one in the downtown core, located on top of a building. Mobile sensors would offer three benefits over the sensors run by Alberta Environment. (1) Real time data that (2) reflects the quality of the air we breathe rather than the AQ on top of a building in (3) locations that we are concerned about.

There is a lot of room to improve the real monitoring of Edmonton, including perceptions of people, changes in the built environment, and changes in environmental quality. To fully understand how change impacts these things, we should start building out understanding of the current (baseline) data soon.

Sense making and storytelling.

One of the limitations to the technology I work with is the inability for users make-sense (sensemaking) of multiple and varied data streams within a mapping or other virtual environment. For instance, within a virtual map space, data may be available that represents map elements in a point, line, polygon or 3D object format. Data may also be available from a sensor network that provides parameters related to environmental or weather indicators, historic or archieved data may also be available, and finally citizens may have hand held sensors or some personal insight / experience with specific locations. How can all of this data be combined to tell a compelling and accurate story of place? This Ushahidi blog provides some interesting links and a compelling story related to personal or organisational narrative where patterns and inferences about content can be made:

http://blog.ushahidi.com/index.php/2011/02/15/hearing-need-and-seeing-change-through-story-cycles/

Imagine collecting thousands of stories like the one above from citizens, community organizers, and NGO staff about what really matters to them … and where change is showing. Now imagine looking through a prism at these stories to find patterns and compare and contrast patterns between community efforts, organisations, burning issues, locations, citizens of different ages, and more.

I find this to be very compelling and interesting. And its a solid step towards creating a sense-making environment where varied data types can be combined.

Hello world!

This is my first post. I am in the process of setting up my website, and will have some content up in the next day or two.